Racial Projects

June 26, 2017

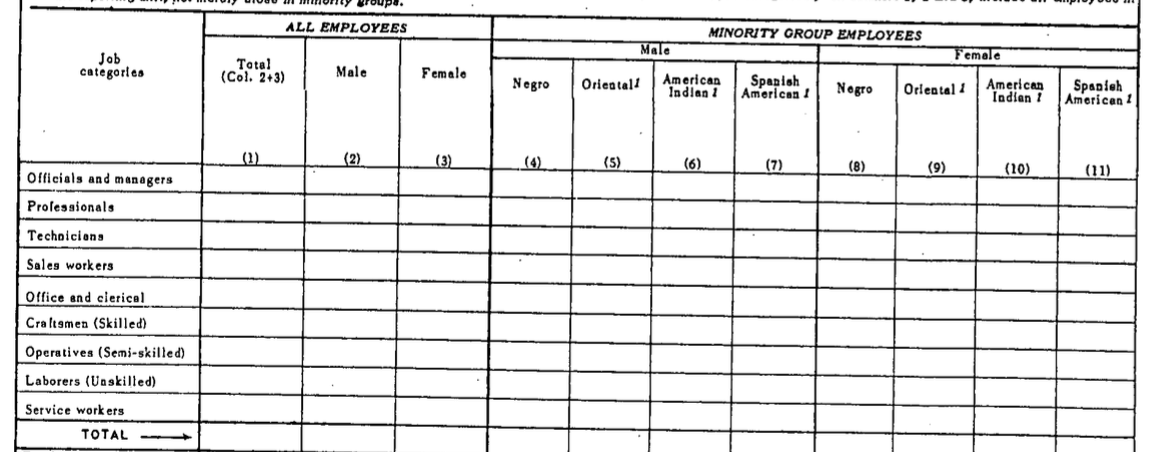

Excerpt from the 1967 Employer Information Report, United States National Archives.

Classifying Racial Ambiguity for Equal Employment

I write this particularly after the Rachel Dolezal phenomenon, with attempts to push forward the conversation on race by asking how it operates through its social construction. At the heart of this story and the fieldwork are debates between identity and race, our tendency to conflate the two, and questions over visibility, narratives, and hypodescendence, or the idea that in the United States race is determined by the “one-blood-rule.” I suggest that the reality of race is and has never been exclusively about identities or bodies. Rather, race emerges through projects (Omi and Winant 1994) that enroll subjects and materialities such as phenotype characteristics, documentation, and statistics in ways that channel actions to create relationships in not always so predictable ways.

I begin this story at the turn of the Civil Rights Movements, which as Roderick Ferguson (2012) has argued, marked a critical moment in the institutional incorporation of difference and the creation of systems of inclusion rather than exclusion. After the affirmative action mandate went into effect, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) created the Employer Information Report (EEO-1) form to ensure compliance. In 1967 for the first time large employers had to document, enumerate, and track the race and gender of employees in the workplace. Today, almost every human resource department across the nation has to file this two-page report, one page of which constitutes a table with five racial categories (determined by the Census) at the top, and the list of possible occupational scales on the left margin.

Excerpt from “Sample EEO-1 Report,” Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2017.

While EEO-1 forms are classified as private and sensitive documents, in the last few years, several corporations have undergone public scrutiny over their diversity demographics. The question of how these numbers become public is at the core of this story on racial projects. Some are able to receive EEO-1 forms by applying pressure to communications departments, others—especially researchers who deal with large amounts of data—duplicate the EEO-1 form by classifying and categorizing each executive member of a corporation by race (and gender).

Classifying individuals by race often entails a process of triangulation. For example, in a study that has now become widely circulated and book, professor of psychology Richard L. Zweigenhaft reveals that most of the Fortune 500 CEO positions filled by non-White males from 2000 to 2014 were attributed to White women. Similar to how other scholars have accounted for their data methodology, Zweigenhaft claimed to have drawn on information available online, and then having corroborated each one of the 4919 racial classications with his peers. He notes, “The interjudge reliability (which is the fancy term for how much the three of us agreed) was quite high—above 99%.”

“The New CEOs by Year: 2000 through January 2014.” Richard L. Zweigenhaft.

I observed such methodologies at play during my fieldwork with diversity coordinators. I watched them organize, plan, and execute hundreds of diversity conferences and workshops across state and country lines for one year. The process of inviting a business executive entailed a meticulous research of their background, documented in a spreadsheet where they matched an executive’s title with a category: Black/African American, Asian American, American Indian, White, Hispanic/Latino.

One day, Susan turned to Stanley, both diversity coordinators, lifted her laptop computer to her shoulder and faced her colleague. The photograph showed a woman with short brown hair and a red suit. She said, “What do you think this person is?”

Stanley: I don’t know—not-white?

Susan: Question mark?

Stanley: [Silence] Hispanic, maybe.

Susan: OK, Hispanic question mark.

Then I heard her thinking aloud, “I have a lot of question marks.”

When I asked Susan to explain how she was certain that the classification she assigned was in fact an executive’s racial or ethnic identity, she said that she “usually can tell.” She described how beyond their pictures she studies their biographies, LinkedIn proles, whether they received diversity awards, and their race- or ethnic-based associations, “such as an Asian Business Society.” When I asked why, she gave me a longer answer explaining, “One time, this woman came at me….yelling, ‘you call yourselves a diversity [organization], and you only had two black women.’ I was like, mmm there were like six.” While for researchers question marks may be omitted from the study, for coordinators question marks are relevant. They gain meaning in relational situations, like in a panel or a workshop, and as such, the question mark acts as a placeholder. Later, Susan, Stanley and other diversity coordinators showed me how “question mark” individuals can still be used, by placing them in panels with more visible racial or gender difference, in effect, giving the impression of “diversity.”

As anthropologists we need to be better about how we conceptualize and theorize race. Steven Gregory and Roger Sanjek (1994) once suggested that many scholars who take “no-real” and socially constructed stances avoid studying race for fears of reproducing it, resulting in what Mukhopadhay and Moses (1997) characterized as a policy of “no discussion of race.” Yet, as Sara Ahmed has argued, “To proceed as if the categories do not matter because they should not matter would be to fail to show how the categories continue to ground social existence” (2012: 182; emphasis original). Particularly for the work of diversity in the workplace, the classification, enumeration, and documentation of race results in or forecloses the possibility for mentorship programs, training, budgets, among other resources. Categorization practices, are always purposeful and often political. Yet, in a post-Civil Rights Era they certainly have been undertheorized as tools of neoliberal inclusion.

Rather than aim to uncover claims of authenticity behind race, I suggest that we study how race emerges from projects such as these. These projects are composed of, as Bruno Latour (1984) has suggested, knowledge accumulation through processes of enrollment, cascades of inscriptions, and trials of reason. In other words, we should orient our questions to how and why some associations and truth-claims have more weight than others, and how individuals create coherent and intelligible objects, such as race and diversity. Hence, I ask of us, how can we reimagine racial materiality not as something that is found, but as that which is enacted? It seems clear, however, that in order to discover something new, as researchers we must do something dicult: suspend what we think we know about race to ask how these categories—that already exist—come to matter.

Acknowledgements: This opinion was first delivered as a paper at the University of Toronto’s Techniques of the Corporation Conference. Thank you to the organizers and participants who provided insightful commentary to this work.

Cite as: Arciniega, Luzilda Carrillo. 2017. “Racial Projects.” Anthropology News website, June 26, 2017. doi: 10.1111/AN.496