Notes on the Political Divide

April 28, 2017

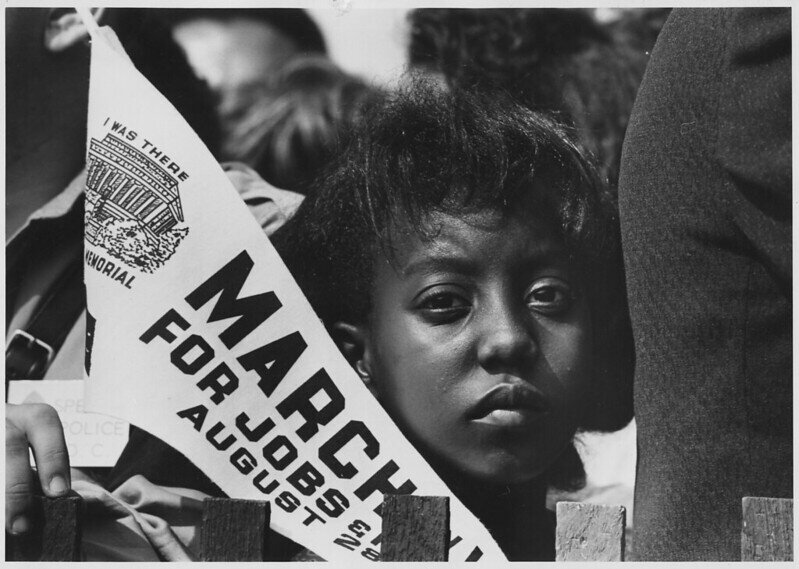

Photograph No. 306-SSM-4C-61-32 (Photographer Rowland Scherman); “Photograph of a Young Woman at the Civil Rights March on Washington, DC with a Banner,” August 1963; Records of the US Information Agency, Record Group 306; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

Disentangling Antiracism from Capitalism

Was it racism or class that gave Trump the election? Much has been written about this topic, including articles that deconstruct the white working-class, analyze the opportunism in whiteness, and claim racism was to blame. Yet, our attempts to understand the rise of Trumpism have not assuaged our fears of institutionalized and interpersonal hate. Rather, many have had to avoid family members and sit though difficult Thanksgiving dinners. While conducting fieldwork, for instance, I heard a diversity coordinator say to her best friend—someone who voted for Trump— soon after the election, “Don’t you care if I am deported?” No answer would have been sufficient. Rather than attempt to provide further speculation or analysis on why people voted for Trump, we should recast the question: why did the election take us by surprise? I suggest that just one of those reasons might be that we have allowed antiracist work under capitalism to go unquestioned.

Antiracism work before the 1970s, such as in the Civil Rights Movements, was largely marked by demands for jobs and education as a means of ending poverty. For example, through marches, strikes, camping and a variety of other tactics, African-American groups joined the Poor Peoples’ Campaign and lobbied for the Voting Rights Act, which sought to eliminate voting discrimination laws and practices, including literacy tests and poll taxes. Subsequent marches on poverty, recently portrayed by the film Selma, paved the way for changes to resource distribution, including through subsequent changes in how the US Census counted racial minorities. Additionally, second-wave feminists rallied around the slogan, “the personal is political” and lobbied for pay equity and established abortion rights through Roe v. Wade. On the west coast, African-American, MexicanAmerican and Chicano/a, and Asian-American groups created a coalition to institute Ethnic Studies programs in order to create and circulate non-white history.

Identity-based organizing is rooted in a struggle for state recognition and economic well-being, but recently we have managed to ignore that within identity (and even racial) groups political and class differences exist. Through my fieldwork in studying diversity management consultants—many of whom were active in the Civil Rights Movement—I found no discussion of economic differences within corporate work. After I had presented research findings on executive leadership demographics, the founder of a diversity consulting firm asked me, “So, what do you think about corporate people now?” I responded with, “The CEO of [a multinational company] is Latino, made six million dollars last year, and doesn’t have a college degree.” He laughed and said, “That’s a very smart man.” In effect, much of diversity management within corporations is oriented to promote the upward mobility of minorities and women into executive positions. Both consultants and those who wish to climb the corporate ladder often revere the income of executives, and purposefully ignore large wage disparities.

Antiracism and capitalism have a complicated historical relationship in the US. Scholars and public commentators studying the integration of minorities and women after the 1960s into existing social structures—including academia, the military, and even Wall Street—claim that as a result of their newfound positioning within institutions of power, these individuals align their identities and subjectivities with the logics of capitalism, allowing wealth inequalities to widen. Furthermore, Jodi Melamed argues that the symbolic representations of women and people of color in high positions of power, including that of Condaleeza Rice and Clarence Thomas, “distracted from deployments of US state power…and its negative effects on the racialized poor in target countries” (2006: 18). Thus, neoliberal multiculturalism, which aims to manage antiracist practices within global capitalism, has demonstrated that symbolic antiracism actually perpetuates and exacerbates systemic racism.

Furthermore, in the last thirty years the structure of work has changed, suggesting that our idea that hard work and determination enables people of color and women to achieve upward mobility is no more than a fantasy. In 1990 a pioneering business scholar and consultant, R. Roosevelt Thomas Jr. wrote that the workforce is already diverse, arguing, “women and minorities no longer need a boarding pass, they need an upgrade.” That is, corporations need to create corporate policies and cultures to optimize individual potential to increase retention, productivity, and profit. Today, many corporate workplaces—and academic ones—are experiencing the minimization of affirmative action policies in favor of diversity and inclusion departments. These emphasize the assessment and creation of employee engagement, development of business professionalism and mentorship and sponsorship plans, and creation of networking opportunities. Scholarly and popular business management literature—much circulated through Harvard Business Review, Forbes, and BusinessWeek—reproduces the work of these diversity and inclusion departments.

Richard Sennett (2007) argues that it is under the new cultures of capital, a transition largely led by corporate work, reward potential, rather than craftsmanship, which takes time to develop. Yet, corporations are unstable, and they are able to rapidly liquidate while turning a profit. In 1920 the average lifespan of a corporation was 67 years, whereas five years ago, it was 15. This makes me question whether all the efforts that potential and current employees are placing on professional development is for naught or for something else.

Regardless, we continue to idolize and aspire to place women and people of color in positions of leadership, without critically questioning current rampant economic inequity. We have prioritized ideals of individual self-fashioning and access to capital at the expense of perpetuating systemic inequity. The Civil Rights Movements and contemporary diversity management did not and will not (at least not in its current form) create the structural changes necessary to eliminate economic, racial, and gender inequity. If anything, the recent election revealed that just about everyone is unhappy with the current economic and social conditions. Now that Trump has won, we have the opportunity to challenge the foundations of neoliberal multiculturalism, in particular because this election demonstrated how class and race have and will always be intersectional.

To be clear, I am not advocating for the bridging of a political divide, which has long been framed as a left-and-right opposition. Instead, I advocate for the expansion of political theorizing and organizing that has long focused on advocating for the most marginalized. Rather than engaging in oppression Olympics, this vision entails looking inward as much as outward to imagine and advocate for an antiracism that is outside of equal access to capital. If we insist on supporting symbolic identity politics, we will continue to mark our own complicity in perpetuating both capitalism and racism.

Cite as: Arciniega, Luzilda Carrillo. 2017. “Notes on the Political Divide.” Anthropology News website, April 28, 2017. doi:10.1111/AN.417