Diversity Audited (A Short How-to-Guide)

February 6, 2018

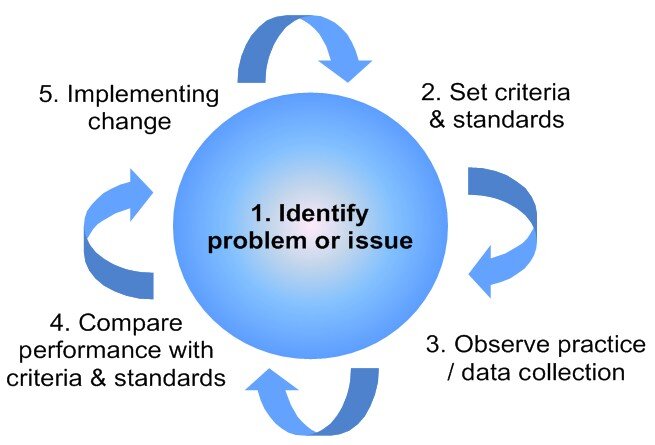

“Clinical Audit Cycle.” Craig.parylo at the English language Wikipedia/ Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Since the 1980s, audits have almost become mundane. They have provided means by which employers can increase efficiency and productivity, as well by which the most disenfranchised can exercise agency. With regards to the latter, documents, numbers, and benchmarks make rights visible and achievable, even if these tools for measurement end up obscuring and simplifying complex issues. Despite limitations, I ask us to turn to diversity audits for inspiration to create better and more inclusive academic departments. Below I present five methods for organizational change: reviewing diversity demographics, creating resource awareness, identifying diversity targets, increasing retention, and creating accountability structures.

(1) Review your diversity demographics

Examine how your bureaucratic procedures reproduce systemic inequities. Ask yourself: are your top choices for graduate student admissions reflecting the diversity mission statement of the department and university? If you can: examine the diversity numbers in the last five to ten years. What were the demographics of those who applied, interviewed, and were accepted? Look for a trend that might be revealing of how the department prioritizes admissions and hiring and identify opportunities for these decisions to support the diversity mission statement. Bring these issues to faculty meetings and schedule a serious conversation about visions for the department and university, including how to address problems in diversity pipelines and create structural support to achieve equity.

(2) Create awareness over resources

Most universities today have diversity and equity departments with affiliated offices and that have comprehensive websites on policies, resources, and processes for establishing equity. Yet, a person can spend hours researching before finding what they need—additional financial aid, a network of scholars, or the appropriate venue to file a complaint. If your department doesn’t already have an internal website to access bureaucratic forms, grant resources, examples of candidacy exams, dissertations, cover letters, etc. etc.— create one! Then add a page for diversity resources, including but not limited to intramural and extramural fellowships, leadership opportunities (e.g., mentorship programs, service councils and affinity groups), disabilities (including mental health!) services, and recurring professional development workshops. Ensure that undergraduates have something similar. Documentation is a useful way to provide students with institutional knowledge, but beware that this does not take replace actual mentoring or advising.

(3) Address retention issues

The following two ways to address retention both have to do with event planning, although that is not the only way: First, educate the department on resources already available. For example, this past fall the University of California, Irvine Department of Anthropology invited Title IX officers to speak to faculty and graduate students (separately) to address the definition of harassment and discrimination, the complaint process, and the rights of complainants and respondents in an investigation. Many said they found them useful: some learned that racial micro-aggressions could be reported and others that the Title IX office could open their own investigations if they established a policy violation pattern. Second, create opportunities to develop student competencies. I am currently planning a two-hour panel with post-fieldwork graduate students to speak on their experiences in the field and with dissertation write up, including negotiating family, work, and life. Another panel idea is to invite senior graduate students and recent graduates to speak on their academic and non-academic job market experiences.

(4) Identify diversity target(s)

Despite diversity being a historical problem, there are always new problems that emerge with changing structural conditions. For instance, in the last five years I’ve known of two graduate students (at different institutions) who were dismissed from their departments for not meeting normative degree deadlines due to disruptions linked to mental health. One of them sued their institution, won, and is now a graduate student again. Unfortunately, it is often the case that lawsuits reveal problems with diversity that are otherwise neglected and/or willfully ignored. Diversity practitioners often anticipate problems by distributing anonymous surveys, asking an external facilitators to hold focus groups (again, anonymously), and last but not least, by examining complaint records. Given the current post-Harvey Weinstein moment, I have to ask, is there a serial harasser that everyone seems to know about, but that has not been addressed?

(5) Create accountability structures

In 2016, I assisted a diversity consultant on a training designed to help a corporation begin to form a nationwide diversity and inclusion department. The training was for over 140 middle managers and was held in two locations, one on the East Coast and one in the West. Each one of them was to lead one regional branch. After being informed that all those attending would be volunteers, we created a survey to assess the competencies, interests, and demographics of those attending and (unsurprisingly) found that most of the participants were women or people of color! We confronted the organizers who immediately recognized the problem: diversity work cannot be sustainable without the distribution of responsibilities beyond those that feel a passion or commitment for it.

To these ends, I suggest creating an accountability structure, even if it is just a spreadsheet: Who will be examine the diversity numbers and report the findings to the faculty meeting? Who will create a resources website? Who will organize the Title IX meeting and ensure there is enough food and drinks for starving students? Without accountability structures and the fair distribution of responsibilities, the work of diversity is too often mapped onto racialized and gendered bodies and reproduced through affective labor.

I am sure few want to hear that yet-another committee needs to be formed to address administrative issues. Yet, I will challenge anyone who doubts that this is some of the most important work of the New Year. I will reiterate: it is not that this work has not being done; rather, the form it has generally taken is unsustainable, and it is often unfairly distributed. Especially, for those of us who are concerned with where the nation seems to be going, I hope that these suggestions can help create more inclusive anthropology departments. Take what you need with the critical awareness that creating change entails, and take advantage of the free resources available out there.

Further Reading:

Hetherington, K. Guerilla Auditors: The Politics of Transparency in Neoliberal Paraguay. Duke University Press, 2011.

Hull, M. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Merry, S.E. “Measuring the World: Indicators, Human Rights, and Global Governance.” Current Anthropology 52, S3 (2011): S83-S95.

Riles, A., ed. Documents: Artifacts of Modern Knowledge. University of Michigan, 2006.

Shore, C. and S. Wright. “Governing by Numbers: Audit Culture, Rankings and the New World Order.” Social Anthropology 23, no. 1: 23-28.

Strathern, M. 2000. Audit Cultures: Anthropological Studies in Accountability, Ethics, and the Academy. Routledge.

Cite as: Arciniega, Luzilda Carrillo. 2018. “Diversity Audited (A Short How-To Guide).” Anthropology News website, February 6, 2018. DOI: 10.1111/AN.759